From my neighbour's

windows

Windows: Part 6

...The drama of a disillusioned man who threw himself out of a tenth storey apartment and whilst falling saw through the windows the private lives of his neighbours, the small domestic tragedies, the clandestine loves, the brief moments of happiness, news of which had never reached the public stairwell, so that at the instant of crashing against the pavement he had completely changed his view of the world and had reached the conclusion that the life he was abandoning for ever by the false door was indeed worth living.

Gabriel García Marquez, Untitled tale, n.d.

The final chapter of this project aimed to let aside my experience with my windows to rather understand those that residents of Bolin Aiyue have with their own. For that, I engaged four former francophone colleagues living in the compound to participate in this investigation, leveraging a convenience sampling approach on location and availability of foreign respondents. Further selection criteria included residency of more than six months and mutual trust between us as researcher and participant. I then conducted semi-structured interviews in the participants’ apartment in late February 2021, lasting approximately 30 minutes each, to gather detailed insights into their past and present window experiences.

In the data collection phase, with a tape recorder in hand, I recorded the interviews to capture nuances in participants’ responses, which facilitated subsequent analysis, and I took photographs and videos of the discussed windows as well as their views, enhancing the visual representation of their narratives. In the data analysis phase, I listened to the interviews several times, then transcribed and analysed them, while I employed post-it notes to synthesise key points from each participant’s responses. Inductive clustering of these points allowed me to identify overarching themes, structure my findings in the following paragraphs and lastly, make a video to visualise parts of our discussions and let the viewer sense, to some extent, my neighbours’ thoughts, stories and ways of seeing their own window.

Profiles and interview structure

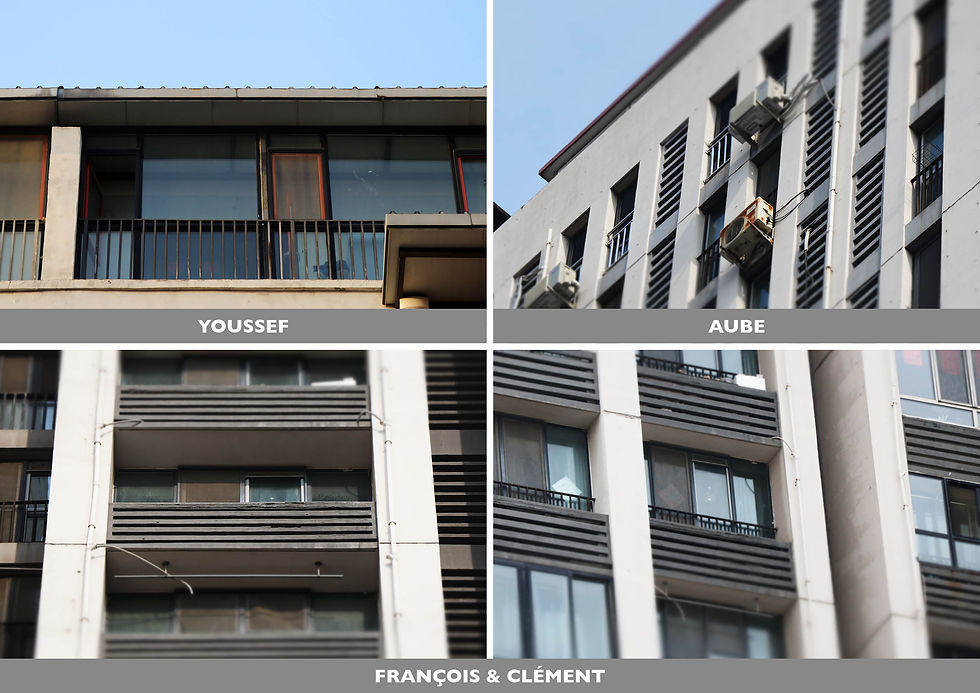

Participants were composed of three males and one female, one of which was Moroccan and the other three were French. At the time of the interviews, Youssef resided on the seventh floor of a smaller building within the complex, having lived there for six months. Aube resided on the nineteenth floor of a twenty-floor building, having resided there for a year and a half. Clément and François resided as roommates on the sixteenth floor of Aube’s building, with Clément there for nearly two years while François for only six months. I encouraged participants discuss their experiences with their preferred window; however, François chose to discuss the window he disliked the least. Selected windows were mainly situated in the living room, apart from Youssef who chose his bedroom window as it was for him the only one available to establish a real bond with. Interviews were therefore structured to progress from descriptions of participants’ observations and opinions of their windows to reflections on their personal preferences for living spaces. This approach facilitated a comprehensive understanding of participants’ relationships with their windows, encompassing their observational skills, understanding of urban environments, personal memories, and imaginative responses to hypothetical scenarios.

Sights and sounds

The four respondents, situated at different heights, could mainly see buildings, streets, cars and pedestrians, indicative of the urban landscape. From their sixteenth floor with south orientation, Clément and François had a panoramic view towards a high school stadium and the cityscape with its huddled buildings. Aube, from her nineteenth floor with west orientation, had a front view on a building, but she could also see inner pathways of the residence by turning her head to the right. As for Youssef, he could see close enough the main pathway of the residence with its trees, cars and residents from his seventh floor with south orientation.

Beyond this objective description of what interviewees observed, their emotions soon appeared when asked about their preferences and dislikes regarding their current view. For Clément and François, the high school stadium and adjacent kindergarten gave vitality to the area when students were around, but François highlighted that otherwise ‘there isn’t much to see as the view is a bit sad with these buildings all around’. Both agreed that the view was rather static, lacking in variety, dynamism, greenery and colours that could arise their curiosity. While Clément said that ‘in ten years the view will still be the same’, he was rather happy with this large window as it gave ‘the feeling of having western style verandas’, offering abundant brightness and a wide perspective which, based on his experience, was quite unusual in China.

Aube appreciated the variety of her window’s view, which blended urban and natural elements, including the scenery and hum of the city, but also the moon, sunrises and sunsets, the movement of Venus and, most importantly to her, the presence of the mountains in the morning when the sky was clear. In Aube’s words, ‘at every moment, something will be missing as it’s the time of the day that reveals or hides what we see’. These variations are part of a routine that calms us all unconsciously by confirming that the Earth is still moving around the Sun and that life goes on outside despite one’s good or bad day. Aube compared her monitoring of these daily cycles to that of a concierge who would ensure that everything remains in order. In contrast, Youssef, deprived of these views and what happened beyond the residence, found enjoyment in a nocturnal habit of counting the windows that, ‘like his’, were still lightened at one or two in the morning, when everyone was sleeping. He certainly appeared more neutral compared to Aube and Clément’s evident enthusiasm or François’s discontentment with their respective views.

A window’s view could evoke both positive and negative experiences. When asked about urban sounds, Aube expressed being ‘relatively deprived from noises’ due to her apartment’s height. While she did perceive the city hum, it did not disrupt her calmness as it made her feel ‘with other humans’. However, when asked about disliked sounds, Aube explained how she investigated for days to identify the source of recurrent shouting. She recounted being scared as she ‘couldn’t understand why these men were shouting that loud and that early’ and thought they were fighting, only to discover it was military exercise nearby. Aube acknowledged her difficulty in filtering out noises, recalling an afflicted dog bark for weeks as other example that she interpreted as signs of distress.

As these sounds were repeatedly heard every day, they became familiar and she got used to them, even detecting the times of the day they had to be heard; late afternoon for the dog and early morning for the military salute. Aube also noted the sound of cats in heat resonating between buildings, concluding that she ‘would like to hear birds’ but she could only hear ‘cats, dogs and people shouting’. When listening to her, I felt that she generally perceived a sense of calm from her windows, although a series of sudden and distinct sounds were often felt unpleasant. Similarly, as François and Clément lived in the same building, they could also hear these cats in heat. François lamented that ‘we rarely hear nice things like music’ while Clément complained about the view of the residence’s landfill and the disruptive noise of dump trucks every week for three or four hours, breaking the ‘monotonous atmosphere’ that they usually had at home, ‘as if suddenly we were moving from one environment to another’.

Functionality

Apart from the view it offers, a window can hold significant value for its inherent qualities. Youssef highlighted several attributes from his double-glazed window as they formed a closed balcony that was ‘like a heater’, comfortable but also practical to dry clothes. He also emphasised on natural lighting as the window helped him waking up earlier, and then, noise isolation, probably due to the double-glazing and for being located inside the residence rather than near the road. Ventilation was another essential aspect for Youssef, as he mentioned the importance of a well-ventilated room and, lastly, he noted the overarching benefit of a window in reducing energy consumption. Natural light reduced the need for artificial lighting, and its heating or ventilation functions could alleviate the necessity of using air conditioners or heaters. Youssef had truly become an expert of his own window through these observations, especially, when mentioning the occasional noises produced by the glass as it cooled down at night after being all day warm, which turned out to be true as I could hear a ‘toc’ every two minutes while interviewing him.

A window can also have the function to change our perceptions of life indoors and outdoors. Initially, the window that Aube discussed with me was not her favourite one as it proved to be too small for her liking during the first months in the apartment, but she found it every time more interesting due to the variety of its view, which started to impact her mood positively. In contrast, Aube thought that the window’s emplacement could allow neighbours to see her and her daughter from the facing building, which incited them to draw the curtain when watching films in the living room. Aube reflected on this need for privacy, remarking ‘I do not want to be seen and I know it’s a way for people to see me’, contrasting this with the earlier sensation of the window as a portal to fly away to the outside world. In a final anecdote, Aube revealed that she had overcome her fear for heights with this nineteenth-floor window, whereas it was her daughter who had to remind her to be cautious when leaning out.

As Youssef earlier, François saw his window as a source of light and ventilation for the living room, allowing him to wake up more easily in the morning. Interestingly, the window served the function of distracting his cat, Robin, when opened, while the mosquito net could protect him from falling. Clément even added that Robin had his ‘own little corner to rest and enjoy the sun’ as they installed a cat window perch. Despite these practicalities, François ironically despised his window once more, claiming it had little effect on his own mood. In contrast, Clément insisted on the virtues of his large windows, which flooded the room with light, and were aesthetically pleasing, seamlessly blending with the apartment’s interior décor. He also noted the skyline’s utility as an indicator of pollution if buildings were covered, and wind intensity if trees were swaying. Further, there was a major divergence between Clément and François regarding the window bars, given that the former appreciated the sense of security they provided while the latter felt they deprived him of his sense of freedom. It was quite amusing to see how the same window could be perceived differently by two individuals living in the same apartment.

The feeling of being in China

Participants brought contrasting perspectives when asked if they felt like being in China when looking through the window. Aube said that, at least, she felt not being in Paris as ‘it doesn’t smell like Paris’, and Clément confirmed that he didn't feel being in France or Europe. Interestingly, Aube was the only respondent who did not strongly associate her window view with China. She described it as ‘a somewhat ugly suburb of Dijon or Brest’ while François suggested it could be mistaken for a Parisian suburb if not for certain details such as the façades, Chinese flags or red stickers on the windows, all characteristic of the Chinese urban landscape. While reflecting on these cultural identifiers, I saw that François, Clément, and Youssef had the Fu character adorning their windows, symbol of good fortune, which Youssef noted as emblematic of Chinese windows.

During the Chinese New Year, Youssef definitely felt like being in China amidst the display of red lanterns, knots and door couplets, all decorative elements integral to the culture and visible from his window, while Clément and François had that same feeling by seeing fireworks from theirs. Further, Clément identified huddled buildings and the absence of shutters as key indicators of being in China, wondering how his neighbours manage to sleep without complete darkness. Aube also acknowledged that when looking into others' apartments, she found ‘people without curtains, who are not hiding, with sad and poorly lit interiors’. At the end, despite being curious to know more about how their Chinese neighbours live, all four participants concurred on the importance of privacy, acknowledging the need to disconnect from the outside world, especially at the end of the day. In a way, it almost feels that ‘home’ is a timeless, spaceless cocoon, which doesn’t necessarily need to be situated in any specific country, unless the outside world calls for our attention and pulls us back to ‘reality’.

Past windows

In the realm of experiences, windows play a pivotal role in shaping our preferences and aversions when it comes to living spaces, influencing our room selection. During their quarantine stay in Shanghai, Aube and her daughter were allocated two rooms with only a few minutes given to visit them. Aube did not take the room with the walled-up window but the one with the bay-like window, around which she created her world. While her daughter did not notice any difference, Aube noticed it instantly and concluded that ‘a window is an eye, a tunnel to go away’. With just a few minutes to decide, windows become a reliable indicator in imagining life in a space.

Similarly, in a past trip to Benin, François was allocated a room with small windows only for ventilation, preventing him from enjoying outside views. Disappointed, he opted to spend his time in an office upstairs with a large bay window and a balcony, as they would provide abundant natural light. Interestingly enough, here are examples of people who still had a choice in selecting their room, but what might occur in situations where options are unavailable? In his first years in Beijing, Clément had roommates who lived in narrow rooms resembling closets, ‘long enough to put a bed and a wardrobe’, and obviously lacking windows—a condition he deemed ‘unthinkable’. Similar to Aube’s experience, he once rent a room in a hotel with a window facing a wall, providing him a glimpse into what it might feel like to be deprived of a view. This is when Clément reinforced his appreciation for the windows in his apartment, particularly during the confinement period from February to May 2020. In this regard, all four participants emphasised the significance of windows during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Our encounters with windows weave together parts of our lives, capturing our fears, frustrations, joys, and aspirations—all sort of memories. François remembered his grandfather’s attic windows as they had bars that restricted his field of vision, contrasting with the playful freedom he found in the skylight of his childhood bedroom. Similarly, Aube recalled her grandmother’s nineteenth century Balzacian house with their bull’s-eye windows, charming from outside but intimidating from inside. Reflecting on her own past, Aube expressed disappointment with the places she has lived in where windows failed to offer expansive views, often showing uninteresting things. Aube always expected windows to satisfy her. Her current window met these requirements as she started to turn her head to the right, but this was not the case initially. Aube concluded saying that before complaining she should better learn to look for what her windows hide; ‘we have to tame each other, I have to tame the sight.’ In her experience, windows have often frustrated her at the beginning but sparked intrigue later on, and it almost feels as if windows should provide the view we want without effort, much like when an audience complains of artworks that hide their deeper meanings. However, when Clément recounted an unusual experience in France where a colony of ladybugs invaded the joints of his sliding windows, preventing him from opening them despite having a pleasant view of a park, it made me think that often external factors, such as pollution or, in this case, ladybugs, can truly hinder a window’s daily usage and frustrate us over time.

Ideal windows

Past experiences and future expectations regarding windows are deeply intertwined, as a positive or negative memory can shape our preferences. For example, growing up in a house with wooden windows, as it happened to Clément, might instil a desire to recover that same feeling of warmth. Our window preferences can also be influenced by personal or collective imaginaries; when asked about their ideal window, most respondents expressed a desire for large bay windows. Youssef and François dreamed of a view overlooking the sea—a terrace with a beach view for Youssef, where he could listen to the sound of breaking waves, and a lighthouse hit by a storm for François. Youssef also yearned for a garden with trees, similar to Clément’s call for more greenery, highlighting the widespread desire for natural surroundings.

It was also interesting to ask participants to explain how they would change their current window through practical examples rather than idealised ones. For example, if only asked to change the view, François would remove buildings to see what is behind, ‘if there is a park or something interesting, something other than buildings’ while having a closer glimpse into people’s daily lives. If asked to change the window’s features, François yearned for a larger window without bars and mosquito nets as well as replacing the dusty curtains into shutters. Additionally, he would have liked to enjoy his cigarette on a balcony, as he could do when he was living in Youssef’s room a year earlier, as it seemed to be a calm ritual that he missed. Lastly, if asked to change a situation affecting their window’s current use, François lamented the inability to fully open them due to his cat, highlighting once more how everyday constraints can reshape one’s relationship with a window.

Participants were asked to envision their ideal windows, which naturally led to discussions about the ones they would avoid. Drawing from their past experiences, I knew François would steer clear of small windows with bars, while Aube and Clément would avoid walled-up windows. However, one’s aversion to certain window types might also stem from what has been observed rather than directly experienced. In this regard, Youssef expressed his dislike for windows that couldn't be closed easily, when it should be their main function, as well as windows directly facing his own, because ‘even if you just want to have a look, you may see other people’s private life’. Youssef then explained his disdain for ground-floor windows for privacy but also security reasons, as they could be easily accessible to intruders.

Life without a window

When asked about the possibility of living in a room without a window, François reflected thoughtfully about it, that windows not only ventilate and provide natural light, but also a connection to the outside world: ‘In itself it is true that the window, through little things, we wouldn't say, but it can incite us to go out in the morning, it can make us want to... Looking out the window, not the window itself, but looking out the window. It will make us want to... It will give us the temperature, if the weather is nice or cold, if I'm putting on a coat, I'm putting on a scarf, or not. I want to go out, I don't want to go out. I see olala there is pollution, I don't go out. Whereas if you don't have a window, you have to look on the Internet, and then, I don't see myself in a room without a window’. It is worth noting that the only participant who continuously expressed dissatisfaction with his window ended up sharing such opinion about its view.

François expressed discomfort at the idea of being physically and mentally confined without a window, and Clément added that ‘even for the mind, the morale, we need some sort of light, we need to see things outside in order to identify with this social, natural mixture’. By letting them imagine how a life without a window would be, led them reaffirm how important windows actually are. François acknowledged that he couldn’t change his windows easily as he could do with curtains: ‘I’m here for an indefinite period, so I have no choice, I have to adopt them as they are, to accept them as they are, with their defects and qualities’. This pragmatic approach reinforced the necessity to accept the windows that we have, here and now, in our everyday reality rather than in our imaginary.

If you are in China, you may have to activate your VPN to watch this video.

Bye bye windows

Rhythms: the music of the City, a scene that listens to itself, an image in the present of a discontinuous sum. Rhythms perceived from the invisible window, pierced into the wall of the façade…But next to the other windows, it is also within a rhythm that escapes it…No camera, no image or series of images can show these rhythms. It requires equally attentive eyes and ears, a head and a memory and a heart. A memory? Yes, in order to grasp this present otherwise than in an instantaneous moment, to restore it in its moments, in the movement of diverse rhythms. Henri Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis, 2013, p.45.

With the insights from my four respondents, I have come to refine what I discovered in the previous chapters, that windows, despite being physical objects, they can be personalised and shaped by our shared experiences with them. Windows are essential for indoors life while keeping us connected to the outside. Alongside doors, they are the shape that can be opened and closed or seen through, situated between what is private and what is public. The sight and sounds they offer are an integral part of our daily routine, while our interactions with them and the stories they hold reveal how they fulfil our needs for light, air and activities, all the while showing us the weather and protecting us from polluted, dusty and stormy days. They remind us, above all, where we are in time and space, inviting contemplation and introspection. Reflecting on windows reveals a certain intimacy and lifestyle that varies from one person to another.

As a researcher and visual practitioner, my approach was inductive, piecing together fragments of information extracted from interviews and observations to inform broader frameworks of thought. As the windows of the residence Bolin Aiyue were my primary interest, interviewing Chinese neighbours could have come to complete the sociocultural interpretation of this project. By interviewing people about their windows, a designer or an architect could rethink interiors and exteriors, while it only gave me, for this project, new perspectives that I could not have explored alone. With this final chapter, the project ended after five months of work, from January to June 2021, although it started unconsciously the moment I first arrived at my apartment on October 2nd, 2017.

With these anecdotes and stories, we are offered endless perspectives to delve into, even more when counting the number of apartments in the residence as they show the even greater proportions that this project could have taken. While some people stay a lifetime looking from or at the same window, my few months of observation have only scratched the surface of understanding them. However, the project’s true value lied in its structured pattern of study, based on these six steps that can be used for future investigations into windows, to then produce a greater quality and quantity of experiments. Finally, much like my previous project ‘Details of a street’ was made before leaving my previous job, and hence the street I walked through during three years, this new project on windows was made knowing that we would have to move at the end of June 2021, after residing in this apartment for three years and a half. This predictable melancholy reappeared under different angles in these three visual projects in Beijing and increased my attachment to specific places of my direct environment while valuing their uninteresting mundanity that is not less representative of life itself.